Contents

- 1 Q.1 Explain The Drainage Characteristics of Panincular India(1994)

- 2 Q2. Explain the geographical factors responsible for the growth of mangrove vegetation in india and discuss its role in coastal ecology.(1993)

- 3 Q3. Delineate the flood prone areas of india by drawing a sketch map in the answer book and discuss the causes and consequences of flood in the North Indian Plains. (1993)

- 4 Q4. Explain the different views put forth about the region of Himalayas into vertical division. (2007)

- 5 Q5. Give a critical account of the recent theories of origin of Indian monsoon with special reference to Jet Stream Theory.(2006)

- 6 Q6. Discuss the role of spatial pattern of rainfall and temperature in the delimitation of climatic regions of india, especially with reference to stamp of climatic regionalization.(2004)

- 7 Q7. Highlight the salient differences between the Himalayan and the Peninsular drainage system. (2003)

- 8 Q8. Explain the origin, mechanism and characteristics of Summer Monsoon in India. (2002)

- 9 Q9. Discuss the relief features of Indian Northern Plains. (2001)

- 10 Q10. Give a brief account of the second-order regions of Indian Peninsular Plateau. (2001)

- 11 Q11. Explain the sequence of vegetation zones of the Himalayas. (2001)

- 12 Q12. Elucidate the mechanism of the Indian Monsoon. (1999)

- 13 Q12. Explain the rise of the Himalayan ranges. (1999)

- 14 Q13. Evaluate the feasibility of the proposed Ganga-Cauveri drainage link. (1998)

- 15 Q14. Draw a sketch-map in your answer-book to delineate the main climatic regions of India and discuss the important climatic characteristics of each region. (1996)

- 16 Q15. Examine the origin and characteristics of the antecedent drainage system of the Himalayas. (1996)

- 17 Q16. Discuss the distribution and characteristics of the evergreen forest in India. (1996)

- 18 Q17. Examine the origin and characteristics of the soils of the North Indian Plain. (1995)

- 19 Q18. Draw a sketch map in your answer book to delineate the main physiographic regions of India and provide a reasoned account of the relief and structure of the Himalayan region. (1995)

- 20 Q19. Describe the structure and relief features of peninsular India. (1995)

- 21 In case you still have your doubts, contact us on 9811333901.

- 22 In case you still have your doubts, contact us on 9811333901.

Q.1 Explain The Drainage Characteristics of Panincular India(1994)

Ans.

There are numerous rivers traversing the Penisnular India, the more important ones being the Damodar, Subarnrekha, Brahmani, Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna, Kaveri and Tamraparni which flow into the Bay of Bengal and form delta. Some rivers like Banas, Chambal, Sindh, Son etc. belong to Katchchh or the Gulf of Cambay.

Following are the chief drainage characteristics of Peninsular rivers:

- Western Ghats, very close to the west coast, is the chief water divide of the Peninsular India.

- However, most of the rivers flow towards the east, the only notable exceptions being Narmada and Tapi which flow in a rift valley.

- The Peninsular drainage has existed for a much longer period than the Himalayan rivers. This is seen in the broad, largely graded and shallow valleys of the Peninsular rivers which is indicative of the fact that they have acquired maturity.

- The beds of these rivers have a very subdued gradient except for a limited tract of the rivers where faulting has steepened the gradient.

- The Peninsular rivers receive water only from rainfall and water flows in these rivers in rainy season only. Therefore these rives are seasonal.

- As such these rivers are not much useful for irrigation.

- Peninsular rivers have small basins and catchment areas.

- Peninsular rivers are although suitable for power generation in their upper reaches but have limited use in irrigation and are not navigable for a major part.

- The hard rock surface and non-alluvial character of the plateau permits little scope for the formation of meanders. As such rivers of Peninsular plateau follow more or less straight course.

- The Peninsular rivers are either superimposed or rejuvenated giving birth to radical, trellis or rectangular drainage patterns.

Q2. Explain the geographical factors responsible for the growth of mangrove vegetation in india and discuss its role in coastal ecology.(1993)

Ans.

Trees have evolved according to specific stresses in the environment. One of these branches of evolution led to plants adapted to high salinity, categorised as halophytes. Halophytes growing in salty marshy areas are called Mangrove vegetation.

The geographical conditions favouring the growth of mangrove vegetation in India are tropical and sub-tropical coastlines—muddy banks of river estuaries, creeks, backwaters and along sea shores. Mangrove vegetation presents an outstanding example of influence of soil-moisture regime on natural vegtation. Trees are adapted to withstand both excess moisture and high salinity. The trees of mangroves have glands on leaves through which salt absorbed by the roots are exuded. The trunk of the trees is fixed in the mud by a number of stilt-like roots which are submerged under mud or water.

The mangrove forests are found in thickest on the western coast at few places but on the eastern coast they form a fairly continuous fringe along the fronts of the deltas of the Ganga, the Mahanadi, the Godavari and the Krishna and along the coast of Andaman islands.

Mangroves are a rich ecosystem and play a major role in the coastal ecology. The habitat of mangroves is extremely conducive to numerous forms of life, thanks to abundance of moisture, nutrients from decaying organic litter, minerals arriving with rivers and abundant sunshine. The shade provided by dense foliage and shelter by profusely branching roots ensure excellent homes for a large variety of organisms like insects, worms, crabs, prawns and fish during growth and especially during breeding periods. Parasites, saprophytes and predators find support in the region. Such kind of biodiversity promotes ecological stability in the region.

Another significant contibution of mangrove vegetation is arresting the movement of soft muds with tidal movements of water, thus providing effective control of soil and mineral nutrients from flowing into the seas. A mangrove vegetation checks the occurence of soil erosion by the tidal and sea waves in the coastal areas.

Mangrove forest assumes paramount significance in case of natural disasters like cyclones and tsunamis. It acts as a bullwork against rushing giant waves, thus reducing their impact considerably on the inland areas. Coastal ecology is thus protected from getting disturbed. The need for preserving the mangrove ecosystem is felt intensely.

Q3. Delineate the flood prone areas of india by drawing a sketch map in the answer book and discuss the causes and consequences of flood in the North Indian Plains. (1993)

Ans.

Flood is a state of high water level that leads to inundation of land which is not normally submerged. Flood is a natural phenomenon but extent of its consequences in recent years has been largely determined by the human activities.

About 40 million hectares of country’s area is prone to floods. Among these areas, the North Indian plain is the worst flood affected region of India accounting for more than 60 per cent of floods in the country. Here Assam, West Bengal, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh are the most flood-hit states.

Causes of floods in the North Indian plains have been discussed below:

- Heavy incessant and prolonged rainfall is the basic cause of floods. As the volume of water increases, the river banks are overtopped and consequently the adjoining areas are inundated.

- Even in Rajasthan, due to sandy nature of the ground and dry climatic conditions, rivers have not been able to carve out proper drainage channels. Hence in the event of sudden rainfall rainwater gets accumulated causing floods and waterlogging.

- The catchment area of major rivers like Ganga, Yamuna etc. is very large. So the volume of water accumulated by such large catchment area also becomes large, thereby increasing the chances of flooding in the consequent stream.

- Most of the important rivers of North Indian plains have a considerable part of their catchment in the Himalayas which is the youngest fold mountains in the world and therefore highly erodible. Water and silt move out of these mountains in explosive waves.

- The catchment of the rivers of Northern plains receive more than 80% of their annual precipitation from June to September. Consequently, the bulk of their annual run off and high sediment load (as high as 80%) is from June to October, resulting into severe floods during this period.

- The steep coverses of these rivers laden with large amount of sediment in the face mountains abrupt flattening of slope when they enter the Northern plains. This considerably retards their sediment carrying capacity and an excessive siltation of their beds follows. This results into raising of the river beds and consequent reduction in the water accomodating capacity of the river valleys, thus enhancing the impact of floods.

- Excessive siltation also obstructs the natural drainage leading to braiding and shifting of the river courses as a recurring feature, e.g. Kosi. This network of abandoned channels serve as spill channels or drainage channels during floods.

- The topography of the region is very flat and there is no sufficient gradient. Hence rainwater gets stranded over vast area of the plains for longer period.

- Some anthropogenic factors have also been responsible for the increased intensity and frequency of floods. First of all, widespread deforestation in the mountainous regions has increased surface run off. This, coupled with exposed mountainous surface devoid of vegetation, results into increased soil erosion in the upper reaches. Hence both surface run off and siltation is increased, the consequences of which has been discussed in the foregoing paras. Thus, wherever man has resorted to indiscreminate deforestation and other constructional activites, as in Siwaliks, Lower Himalayas, Chhotanagpur Plateau (Damodar river-the sorrow of Bengal), etc. floods have become a rule in the downstream areas.

- Badly planned construction of bridges, roads, railway tracks and other developmental activities have caused drainage congestion in the rivers of North Indian plains. Such drainage congestion obstructs the natural flow of water in the river and thus accentuates the problem of floods.

- Construction of embankments, especially without proper care and maintenance, instead of solving the problem sometimes compounds the problem of floods. Embankments encourage human occupation of the flood plains by instilling a false sense of security. When rivers in spate breach the embankments, the nearby villages are flooded.

Consequences of Floods in Northern Plains:

Floods though come for a short period but they in fact result into far reaching and long lasting consequences. Inundating a large part of the North Indian plains, these floods inflict a huge loss of life and property.

Floods are a major cause of human misery in the North Indian plains every year. The most flood prone areas coincides with the thickly populated and fertile areas of the plains, thereby compounding the extent of damage. Due to increased pressure of population on land, poor farmers are pushed to marginal lands close to rivers. So the principle ‘where a river has a right of way stay out of its way’ is not followed and human habitation close to the river or in the flood plains are devastated by floods.

Hence several lives are claimed by this natural-cum-man made disaster every year and lakhs of people are devoid of one of their basic needs-shelter. Rural areas are the worst affected where acute food crisis and absence of drinking water make the lives of surviving people pathetic.

Such is the extent and intensity of floods in the Northern plains, especially in the middle and lower Ganga plain that the administration gets haywire and often collapses in providing the relief to flood victims—thanks also to lack of efficiency in administrative set up. Whatever inadequate infrastructure exists in the region is severely damaged by the floods—one of the reasons of eternal poverty in the region. Breakdown of transport and communication network and other essential services further disrupts the relief operations. Restoration of these services costs crores of rupees every year.

Other consequences include devastated agriculture in this fertile region and loss of livestocks. Flood water stagnates for longer periods in these flat plains, often resulting into epidemics. Micro organisms proliferate and higher order organisms face the ecological imbalances.Floods turn out to be a social disaster as well for the poor areas of plains. They affect the poor more than the rich.

Q4. Explain the different views put forth about the region of Himalayas into vertical division. (2007)

Ans.

The Himalayas are one of the most complex mountain systems of the world. They represent a great variety of rock system dating back from Cambrian to Eoceneperiods and bear all important types of rocks.

The origin of Himalayas has been as complex as their relief features. There are two primary views regarding the origin of Himalayas:(i) the Geosynclinal evolution; and (ii) the Plate Tectonics evolution.

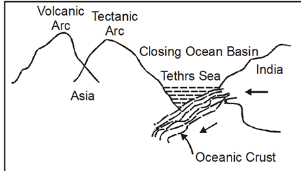

Geosynclinal Theory: As per the Geosynclinal evolution, put-forth by the scholars like Sues, Argund, Kober, etc., the rocks of Himalayas are primarily of marine origin and contain fossils of marine organisms. The disintegration of Pangea led to the formation of a long Tethys Sea between Angaraland and Gondwanaland. Approximately 180 million years ago, the Tethys Sea occupied the region of Himalayas during the Mesozoic era.

The deposition from two land masses started and the sea bed started rising. During the Cretaceous period, the bed of sea started rising which led to the formation of three parallel ranges of Himalayas.

(ii). Plate Tectonics Theory: This theory was found to be a rational explanation to the origin of the Himalayas. It refers to the capability of lithospheric plates’s motion over asthenosphere. An oceanic crust moving against the continental curst goes underneath it. This process is called “subduction”. Subduction exerts a lot of pressure on the downgoing oceanic crust and leads to melting. This melting leads to the formation of volcanic magma which erupts tearing the relatively weak continental lithosphere.

According to the Plate Tectonics view, given by Hary Hess, Morgan and Le Pichon etc., the rise of Himalayas is viewed as the outcome of collision of Indian plate with Eurasian plate. About 70-65 million years ago, the Tethys Sea began to contract due to convergence of these two plates. Around 60 million years ago, the Indian plate started subducting under the Eurasian Plate. This caused compression and sediments squeezed into three parallel ranges i.e. the Greater Himalayas, the Middle Himalayas and the Siwalik.

Infact, this process is still going on and the Himalayas are still getting higher as the Indian plate is moving under the Eurasian plate.

The Himalayas represent a unique feature over the earth’s landscape. They are well-distinguished in terms of relief, rocks, elevation and strata, both horizontally and vertically.

The verticle division of Himalayas may be considered as under:

- Kashmir Himalayas: North of Indus river is known as Kashmir Himalayas which consist of Karakoram range in the north, Ladakh plateau, the valley of Kashmir and the Pir Panjal range. Banihal is an important pass.

- The Punjab Himalayas: This part has important passes like Zojila, Rohtang and Bara Lapcha La. Kangra, Lahul and Sipti valleys are known for their scenic beauty. Beas and Sutlej rivers have their sources.

- The Kumaon Himalayas: This portion has important peaks like Nanda Devi, Trishul, Badrinath and Kedarnath. Gangotri and Yamunotri lie in this part.

- Nepal Himalayas: The range between Kali and Teesta rivers is known as central or Nepal Himalayas. Important peaks are Dhaulagiri, Annapurna, Mt Everest and Kanchanjunga.

- Assam Himalayas: The portion from Teesta to Brahmaputra is known as Assam Himalayas. Dihang river cuts through the deep gorge in the Himalayas at Dihang. Himadri is in the northwest-southwest direction. Siwalik range is forested and rises abruptly above the Brahmaputra valley.

The Himalaya chain consists of three parallel ranges, with the northern-most range known as the Great or Inner Himalayas:

(a) The Great Himalayas lie north of the Lower Himalayan Range. These mountains are bounded by

the Indus River in the north and the west as the river takes a southward turn at Sazin. The average height of the range is about 6000 meters. Some of the highest peaks in the world lie in these mountains e.g. Nanga Parbat (8126 meters), which is the sixth highest peak in the world and the second highest peak in Pakistan. Since the mountains are perpetually covered with snow there are many glaciers, with Rupal Glacier being the longest (17.6 km).

The glacial action has created many beautiful lakes like the Saiful Muluk lake which lies in the upper Kaghan Valley. Other noticeable geographic feature of this area are the deep gorges carved by the Indus in this region. The deepest of which, located at Dasu-Patan region (Kohistan District), is 6500 meters deep.

(b) The Lower Himalayan Range (also known as the Lesser Himalayan Range) lies north of the Sub-Himalayan Range and south of the Great Himalayas. The height of the mountains varies between 1800 to 4600 meters. Thousands of years of folding, faulting and overthrusting has led to the formation of these mountains. They are a part of the three ranges that traverse from East to West in the Himalayas.

(c) The Sivalik Hills also known as the Sivalik mountains and sometimes called Churia or Chure Hills or Outer Himalaya are the southernmost and geologically youngest east-west mountain chain of the Himalayan System. The Sivalik Hills crest at 900 to 1,200 meters and have many sub-ranges. They extend 1,600 km from the Teesta River in Sikkim, westward through Nepal and Uttarakhand, continuing into Kashmir and Northern Pakistan. The Mohan Pass is the principal pass accessing the Sivalik Hills from Saharanpur in Uttar Pradesh to Dehra and the hill station of Mussoorie in Uttarakhand.

Eastward they are cut through at wide intervals by large rivers flowing south from the Himalaya. Smaller rivers without sources in the high Himalaya are more likely to detour around sub-ranges. There are vast networks of small rills and channels to form streams which are of ephemeral (transient) in nature.

Q5. Give a critical account of the recent theories of origin of Indian monsoon with special reference to Jet Stream Theory.(2006)

Ans.

The theories regarding the monsoons are generally dividend into two broad categories:

(a) Classical Theory; and (b) Modern Theory.

- Classical Theory: Monsoons are mentioned in our old scriptures like the Rigveda and in the writing of several Greek and Buddhist scholars. The credit for the first scientific studies of the monsoon winds goes to Arabs. Al Masudi, an Arab explorer from Baghdad, gave an account of the reversal of ocean currents and the monsoon winds over the north Indian Ocean.

- Modern Theories: The theories developed and propounded by modern geographers are the following:

1. Thermal Concepts: The thermal concept of the origin of monsoon was first propounded by Halley in 1686. According to this concept, monsoons are the result of heterogenous character of the globe and differential seasonal heating and cooling of the continental and oceanic areas.

During northern winter when the sun becomes vertical over the tropic of capricorn in the southern hemisphere, high pressure areas are developed over Asia due to very low temperature. Two bold high pressure areas are developed near Baykal Lake and Peshawar. On the other hand, low pressure centre is developed in the southern Indian Ocean due to summer season and related higher temperature in the southern hemisphere.

In winter, the sun shines vertically over the Tropic of Capricorn. The north-western part of Indiagrows colder than Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal and flow of the monsoon is reversed. In summer the sun shines vertically over the Tropic of Cancer resulting in high temperature and low pressure in Central Asia while the pressure is still sufficiently high over Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal. This induces air flow from sea to land and brings heavy rainfall to India and her neighbouring countries. These are called south-west monsoon or summer monsoon.

2. Dynamic Concept: This concept was propounded by HFlohn. Scientists have refuted the thermal origin of monsoon and have raised the following objections against the old concept or thermal concept:

- If the “lows” developed over the land areas are ”heat lows”, they should remain stationary at their places for some time but they are never stationary. There is sudden and widespread shifting in their positions. The low pressures are related to thermal conditions, rather they represent cyclonic ‘lows’ associated with the South-West-monsoon.

- The rain producing capacity of monsoon winds is also doubtful. In fact, the monsoon rainfall is associated with tropical disturbances.

- If the monsoons are thermally induced, there should be anti-monsoon circulation in the upper air. Such upper air winds which change their directions seasonally are called upper air monsoon. Tropical convergence is formed due to convergence of north-east and south-east trade wind near the equator. This is called Intertropical Convergence (ITC).

3. Air Mass Theory: The south-east trade winds in the southern hemisphere and the north-east trade winds in the northern hemisphere meet each other near the equator. The meeting place of these winds is known as the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). Satellite imagery reveals that this is the region of ascending air, maximum clouds and heavy rainfall. The location of

ITCZ shifts north and south of the equator with the change of season. In summer season the sun shines vertically over the Tropic of Cancer and the ITCZ shifts north – wards.

4. Jet Stream Theory: Jet stream is a band of fast moving air from west to east usually found in the middle latitudes in the upper troposphere at a height of about 12km. The wind speeds in a westerly jet stream are commonly 150 to 300km p.h. with extreme values reaching 400km.

5. M.T. Yin-(1949): his theory of origin of monsoon expresses the opinion that the burst of monsoon depends upon the upper air circulation. The low latitude upper air shifts from 90°E to 80°E longitude in response to north – ward shift of the western jet stream in summer. The southern jet becomes active and heavy rainfall is caused by south-west monsoon.

6. P.Koteswaram: His ideas about the monsoon winds are based on his studies of upper air circulation. He has established a relationship between the monsoon and atmospheric conditions prevailing over Tibet an plateau. Tibet is an ellipsoidal plateau at an altitude of about 4000 m above sea level with an area of about 4.5 million sq km.

Koteswaram supported by Flohn, feels that because the Tibet plateau is a source of heat for the atmosphere, it generates an area of rising air. During its ascent the air spreads outward and gradually sinks over the equatorial part of the Indian ocean. At this stage the ascending air is deflected to the right by the earth rotation and moves in anti-clockwise direction leading to anticlock condition in upper troposphere over Tibet around 300-200 mb (9 to 12 km). It finally approaches the west coast of India as return current from a south-westerly directionand is termed as equatorial westerlies. It picks up moisture from the Indian Ocean and causes copious rainfall in India and adjoining countries.

The Easterly Jet Stream was first inferred by P. Koteswaram and P.R.Krishna in 1952 and aroused considerable interest among tropical meteorologists.

Winter season has outblowing surface wind but aloft the westerly airflow dominates. The upper westerlies are split into two distinct currents by the topographical obstacle the Tibet plateau. Two branches reunite off east coast of China. The southern branch blows over the northern India. In summer in the month of March, the upper westerlies start their northward march but whereas the northerly Jet strengthens and begins to extend across central China and into Japan, southerly branch remains positioned south of Tibet.

7. T.N. Krishnamurti: He used data of upper atmosphere to calculate the patterns of divergence and convergence at 200 mb for the period of June-August. He observed an area of strong divergence at 200m over the northern India and Tibet.

8. The great MONEX was designed to have three components considering the seasonal characteristics of monsoon.

- Winter Monex from 1 December 1978 to 5 March 1979 to cover the eastern Indian Ocean and the Pacific along with the land area adjoining Malaysia and Indonesia.

- Summer Monex from 1 May to 31 August 1979 covering in the eastern coast of Africa, the Arabian branch Sea and Bay of Bengal along with adjacent land mass.

- West Africa monsoon experiment over western and central part of Africa from 1 May to 31 August 1979.

International Monex Management Centres (IMMC) were set up in Kualalumpur and new Delhi to supervise the winter and summer components of the experiment.

9. Teleconnection, the southern oscillation and the EL Nino: Recent studies have revealed that there seems to be a link between meteorological events which are separated by long distance, and large intervals of time. They are called meteorological teleconnections.

10. EL Nino: El Nino is a warm current which apears off the coast of Peru in December. The El Nino phenomena, which influences the Indian monsoon, reveals that when the surface temperature goes up in the southern Pacific Ocean, India receives deficient rainfall.

11. Southern Oscillation: The name ascribed to the curious phenomena of Sea-Saw pattern of Meteorological changes observed between the Pacific and Indian Ocean. This great discovery was made by Sir Gilbert Walker in 1920. When the pressure was high over equatorial south Pacific, it was low over the Indian and Pacific Ocean that gives rise to vertical circulation along the equator with its rising limb over low pressure area and descending limb over high pressure area. The location of low pressure and hence the rising limb over Indian Ocean is considered to be conditional to good monsoon rain in India. Some of the predictors used by Sir Gilbert Walker are still used in long-range forecasting of the monsoon rain-fall.

Origin of Indian Monsoon and Jet Stream: Studies of Indian monsoon after 1950 have revealed that its origin and mechanism are related to the following facts:

- The role of the position of the Himalayas and Tibetan plateau as mechanical barrier or as high-level heat source.

- The existence of upper air circumpolar-whirls over north-south poles in the troposphere.

- The circulation of upper air jet streams in the troposphere.

- Differential heating and cooling of huge land mass of Asia and Indian Ocean.

The studies of air circulation in the middle and upper troposhere have shown that the monsoon is a complex air circulation system.

The general direction of air movements over Asia is from west to east. The equatorward winds of this upper air whirl are called jet streams. The Jet stream blows in a meandeing course. The arctic upper air whirl becomes more prominent and active during winter season in the northern hemisphere and thus the upper air westerly jet streams are established in the latitudinal zone of 20°-35°N.

At 12 to 13 km the upper level winds attain speeds exceeding 180 km per hour. There are two types of jet streams:

- Westerly jet streams which blow from west to east at the height of 12 km; and

- Easterly jet streams which blow east to west at 13 km from the earth surface.

The position of these jet streams changes sesasonally. The easterly jet stream blows to the south of 25°N parallel during the south west monsoon. In June it blows over the southern part of the peninsula and has a maximum speed of 90 km per hour. In August it is confined to 15°N parallel and in September up to 22°N parallel. the easterlies normally do not extend to the north of 30°N parallel in upper troposphere.

The axis of jet stream shifts northwards and south wards at different times of the year. The sub-tropical westerlies that moves eastwards over north India during winter month are known as Western disturbances in India. The westerly troughs and the associated low level cyclonic storms originate in the Mediterranean sea or the east Atlantic region. The western disturbances move acorss north India even in the hot weather season. Then they are associated with violent dust storms over Pakistan and northeast India and with violent Norwester over northeast India and Bangladesh.

They are not very frequent during the season of retreating monsoon but are responsible for recurrence of tropical cyclones of the Bay of Bengal.

Q6. Discuss the role of spatial pattern of rainfall and temperature in the delimitation of climatic regions of india, especially with reference to stamp of climatic regionalization.(2004)

Ans.

Although India’s climate is broadly of tropical monsson type but vast size of the country, topographical differences, impact of sea, etc. have deep impact on climatic elements to exhibit marked variation and thereby create climatic variety at sub-regional level.

Among the climatic elements that exhibit spatial variation, the pattern of rainfall and temperature may provide the main basis for the delimitation of climatic regions of India. For example, the rainfall characteristics show various distinct regimes such as pre-monsoon plus monsson in Assam type typical seasonal monsson type, arid and semi arid conditions of Rajasthan type, more winter rains in Tamil Nadu coast type etc. Similar variations may be observed in the spatial pattern of temperature also. Moreover the data related to rainfall and temperature can also be obtained and applied easily.

L.D. Stamp, on the basis of 18°C isotherm for the month of January, which almost follows the Tropic of Cancer divided India into two major climatic regions—(a) Sub-tropical (continental) and (b) Tropical. The sub tropical India is further divided into five and the tropical India into six (total 11) climatic regions on the basis of rainfall variation.

(a)Sub-Tropical India

1. Himlayan Region: This region includes the Himalayan mountain region where altitude of the terrain greatly affects the distribution of temperature. Upto an height of 2450 metre the average temperature of the winter season ranges from 4°C to 7°C and that of summer season from 13°C to 18°C. The amount of rainfall decreases from east to the west. Western parts also receive rainfall during winter season and on high altitudes the precipitaiton is in the form of snowfall.

2.North-Western Plateau: In this climatic region lying north-west of Satluj river, the average temperature of the winter season is 16°C (at times falling below freezing point). The average temperature of warmest month reaches 34°C and annual rainfall is 40cm. Temperate cyclones during winter season play a significant role in the precipitation.

3.North-Western Dry Plains: Covering western Rajasthan, Kachchh and south western Haryana, here winter temperature is 13°C–24°C but summer temperature shoots up to 46°C. The rainfall is scanty, averaging 5cm/year.

4.Area of Medium Rainfall: In this region covering Punjab, Haryana, Western Uttar Pradesh, Eastern Rajasthan and Northern Madhya Pradesh, the average winter temperature ranges from 15°C to 17.2°C and that of summer 35°C giving high annual range of temperature. The annual rainfall varies between 40 to 80 cm showing summer maxima.

5.Transitional Plains: The average temperature of this region covering the middle Ganga Plain ranges from 16°C—18°C in winter and about 35°C in summer. The annual rainfall varies from 100 to 150 cm whose 90% is obtained during summer season by south west monsoon.

(b)Tropical India

6.Region of very Heavy Rainfall: It covers the North-East India where average annual rainfall is above 250cm and average temperature in 27°C. The region receives most of its rainfall during summer season from the Bay of Bengal stream of the monsoon.

7.Region of Heavy Rainfall: It includes West Bengal, Orissa, South Eastern Jharkhand, Eastern Andhra Pradesh and South-eastern Madhya Pradesh. The annual rainfall varies between 100 to 200 cm deteriorating towards the west and the south. The average winter temperature ranges from 18°C to 24°C and summer from 29°C to 35°C.

8.Region of Medium Rainfall: It covers south eastern Gujarat, south western Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. Annual rainfall is less than 75 cm due to rain shadow location of Western Ghats. The average temperature of summer season is 23°C and that of winter from 18°C to 24°C.

9.Konkan Coast: Extending from mouth of Narmada to Goa, it experiences more than 200 cm of rainfall. The average temperature of this marine climate in January hardly falls below24°C and hence the annual temperature ranges is very low (3°C).

10.Malabar Coast: It stretches from Goa to Cape Comorin, characterised by very high annual rainfall of up to 500cm. The annual average temperature is 27°C exhibiting slight seasonal change.

11.Tamil Nadu Coast: This climatic region covers the coromandal coast having annual rainfall between 100-150 cm whose major part is received during winter by the retreating monsson. The winter season average temperature is 24°C and the annual range is very low (3°C).

The climatic regionalisation provided by Stamp and Kendrew is very simple based on the spatial pattern of variation in precipitation and temperature. This basis of division is sound and reasonable as well.

Q7. Highlight the salient differences between the Himalayan and the Peninsular drainage system. (2003)

Ans.

India is a country of large extent having a variety of relief features, geological structures and climatic conditions. Owing to these factors and a long geological history, the rivers of India have formed varied drainage systems. On the basis of its mode of origin and geographical characteristics, the Indian drainage may broadly be divided into two categories:

(i) Drainage system of rivers originating from Himalaya mountain

(ii) Drainage system formed by the rivers of peninsular plataeu.

There is marked difference between the Himalayan and Peninsular rivers, which is the result of variation in topography, geological history and climate of the area, they traverse.

- Most of the Himalayan rivers originate on the southern slopes of Tibetan highland and first flow parallel to the main axis of the mountains and then take a sudden bend towards the south carving out deep gorges across the mountain ranges to reach the northern plains of India. Such deep gorges by the Indus, Satluj, Alaknanda, Gandak, Kosi and Brahmaputra suggest that the rivers are older than the mountain themselves thus having antecedent characteristics.

- On the other hand, Peninsular rivers have existed for a much longer period of time than the Himalayan rivers. Most of the rivers, such as Subarnrekha, Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna, Cauveri, etc flow towards the east, notable exceptions being the Narmada and Tapi rivers which flow westward in the faulted throughs.

- There is difference in the way, Himalayan and Peninsular rivers have evolved. Formation of Shivalik by the thick alluvial deposits consisting of sands, clays and bolder conglomerates have led geologists, especially E.H. Pascoe and G.E. Pilgrim (1919), to believe that such amount of deposits were laid down by a mighty stream, called Siwalik or the Indobrahm river. The present system of Himalayan rivers is regarded by these geologists as the dismemberment of this mighty Indobrahm river which flowed from east to the northwest-from Assam to the Punjab.

- In case of Peninsular rivers, before the rise of Himalayas, probably the Sahyadri-Arawali axis was the main water divide in the then Gondwana land. However, the submergence of the half of Peninsula lying west of the western ghats below sea level during early Tertiary period disturbed the generally symmetrical plan of the rivers on either side of the original water divide.

- Himalayas are young mountains of high elevation and therefore, its rivers exhibit youthful characteristics, still busy in dippening their valleys. These rivers have carved out gorges and V-shaped valleys across the Himalayan ranges.

- Since, the Peninsular block has largely remained stable and there has not been upliftment for a very long time (unlike Himalaya), it has a senile topography consisting of low hills and plateaus. Rivers here have reached a mature state of development and exhibit more or less graded profiles. They flow through open shallow valleys and have reached almost their base level stage.

- The Himalayan rivers rise in high mountains with their sources in glaciers which give them regular supply of water throughout the year. The sources of Peninsular rivers lie in plateau and low hills devoid of snow, therefore most of these rivers carry very little water or become dry during summer season.

- The river capturing and shifting courses are typical phenomena of the Himalayan rivers. River capturing is mainly caused by the headward erosion of the river and is very common in mountainous area like Himalayas.

- The hard rock-bed and the pre-dominantly non-alluvial character of the plateau surface hardly allow any significant meandering of Peninsular rivers. Many of the Peninsular rivers have straight and generally linear courses.

- Himalayan rivers aided by the bold features of Himalayan relief, continue to perform intensive erosional activity as is evident from the huge loads of sand and silt transported by them anually.

- On the other hand, the smooth longitudinal profiles of the Peninsular rivers indicate that they have very little erosional activity to perform. Consequently, they carry lesser amount of sediment with them.

- Since, Himalayan rivers get water from both glaciers and monsoonal rain, they carry large volume of water, which together with enormous loads of rediment, make the courses of rivers prone to the menace of floods, especially in the great plains of India.

- In case of Peninsular rivers, the problem of flood is not so acute as they flow through hard rock-beds and carry lesser amount of water and sediment.

- The Himalayan rivers have very large basins and catchment areas. They have long courses flowing through the rugged mountains, level plains and marshy deltaic tracts.

- The Peninsular rivers have small basins with well adjusted valleys. These rivers are mostly smaller flowing through plateaus and narrow coastal plains.

- As antecedent Himalayan rivers engage in intense valley depening, they enter the plains, they develop parallel drainage pattern in the upper plain, meandering pattern in the middle and deltaic pattern with distributaries in the lower plains.

- The Peninsular rivers are either superimposed (Chambal,. Son etc) or rejuvenated, giving birth to radial, trellies or rectangular drainage patterns.

- No river of the Himalayan region is a tributory of the Peninsular rivers but some Peninsular rivers are tributaries of the Himalayan rivers, e.g. Chambal, Sind, Betwa, etc. are tributaries of Yamuna and in turn Ganga river system.

- The waters of the Himalayan rivers are utilised for power generation in hilly areas and for irrigation, drinking water and inland navigation in the plains.

- The Peninsular rivers are though suitable for power generation, they have limited use in irrigation and navigation (due to non-perrenial character and hard, rugged surface of the plateau).

- The Himalayan rivers pass through plains whose alluvial soils act as huge reservoir of ground water.

- The rocks of the Peninsular region are hard and impermeable, where the supply of ground water is limited.

- The Himalayan rivers form a number of rapids and waterfalls only in their hilly courses. In the plains the slope is very gentle.

- The Peninsular rivers have great potentials for power generation almost throughout their courses in the plateau region.

- The Himalayan rivers have formed vast fertile alluvial plains, which have supported intensive agriculture and dense population.

- In the Peninsular regions, such conditions are available in some favourable areas and coastal tracts only. Elsewhere in the plateau region, the population is not so dense.

Q8. Explain the origin, mechanism and characteristics of Summer Monsoon in India. (2002)

Ans.

The climate of India is described by just one word “monsoon”. The word conveys comprehensively the idea of rythm of seasons and the changes that occur in the direction of winds. These changes lead to the changes in the seasonal distribution of rainfall and temperature.

Derived from the Arabic word ‘Mousam’, monsoon implies a seasonal reversal in the wind direction throughout the year. They flow from land to sea in the winter and from sea to the land in summer. The later one is called the ‘summer monsoon.’

Systematic study of the causes of rainfall in the South Asian region help to understand the monsoon phenomenan and its aspects, such as :

Origin, onset and landward advance of monsoon.

- Rainbearing systems & distribution of rainfall.

- Break in the monsoon.

- The retreat of southwest monsoon.

- Onset of North-East monsoon.

The onset of South-West monsoon is highly complex phenomenan and there is no single theory which can explain it fully. It is believed that the differential heating of land and sea during the summer months is the mechanism which sets the stage for the monsoon winds to drift towards the sub-continent. The large landmass to the north of Indian Ocean gets intensely heated during April and May. This causes an intense low pressure in the north western part of the sub-continent. Since, the pressure in the ocean to south of the landmass is high, the low pressure cell attracts the South-East trades accross the equator. These conditions are favourable for a northward shift in the position of the ITCZ (Inter Tropical Convergence Zone). The South-West monsoon or the summer monsoon may, thus, be seen as a continuation of the south-east trade winds deflected towards the Indian subcontinent after crossing equator. The Monex expedition revealed that the south-east trades normally crossed the equator between 40°E and 60°E.

The establishment of low pressure over the northwestern part of the Indian sub-continent has some link with the northward shift of the ITCZ. The position of ITCZ is also related to the phenomenon of the withdrawal of the westerly Jet stream from its position over the North Indian plain, south of the Himalays.

The easterly Jet stream sets in only after it has withdrawn itself from the region. However, this relation is quite complex. The easterly Jet streams ows its origin to the summer heating of the lower atmosphere above the Tibetan highlands. With the northward shift in the portion of the sun, the air above these highlands is heated. The radiation from this elevated landmass gives rise to a clockwise circulation in the middle troposphere. The two streams of air flowing out of this landmass at the troposphere level take oppsite directions. One of them flows towards the equator probably to replace the air that crosses the equator at the surface level, while the other is defleced towards the pole. The equatorward flow from these highlands, prevails over India as the easterly Jet stream, while the poleward outflow prevails of East Central Asia as the westerly Jet stream. Thus, it is clear that Himalaya and Tibet play an important role in meteorological conditions leading to the development of the southwest monsoon. Besides the easterly Jet streams steers into India, the rain bearing cyclones which cause widespread rainfall.

The southwest monsoon engulfs the entire sub-continent by mid July. It sets in over the Kerala coast by 1st June and moves swiftly to reach Mumbai and Kolkata by 10th and 13th June.

The rain comes in spells. The hot spells are not continuous and often breaks takes place in their continuity. The tropical depressions originating in the Bay of Bengal, or further east in the South China Sea cause rainfall over the plains of north India. On the other hand, Arabian Sea current of the South-West monsoon brings rain to the west coast of India. Much of the rainfall is orographic as the moist air rises along the Western Ghats. The intensity of rainfall over west coast of India is however related to the offshore meteorological conditions and the portions of the equatorial Jet stream along the eastern coast of Africa.

The frequency of the tropical depression originating from the Bay of Bengal varies from year to year. Their tracks are determined by the oscillating ITCZ. This causes wide fluctuation in the direction and the paths there depressions take, intensity of rainfall as well as the variations in the amount of rainfall. The rains display a declining trend from west to east-north-east over west coast and from east-south-east towards the north-west over Ganga plains.

Break in monsoon (the dry spell) is another characteristic of the summer monsoon, which occurs due to failure of proportional depressions, winds blowing parallel to coast and position of ITCZ. Inversion of temperature in Rajasthan causes dry spells.

By September, South-West monsoon retreats. The retreating monsoon picks up moisture from Bay of Bengal and establishes itself over the Tamil Nadu coast as North-East monsoon.

Q9. Discuss the relief features of Indian Northern Plains. (2001)

Ans.

The Indian Northern Plains or the Great Plains is a transition zone between northern mountains and peninsular uplands in the south. It is an aggradational plain (depositional plain) formed by the depositional work of three major river systems viz. the Indus, the Ganga and the Brahmaputra, hence, also known as Indo-Gangetic- Brahmaputra plain.

The great plains of India is the largest alluvial tract of the world extending for a length of 3,200 km. from mouth of Indus to mouth of Ganga, of which Indian sector comprises 2,400 km. It’s width varying from 150-300 km. decreases eastward. It covers a total area of 7.8 lakh sq. km. The thickness of the alluvial deposit varies from place to place. According to recent computation of seismic sounding, the minimum depth of the alluvium is about 6,100m.

The Great plains is characterised by extremely low gradient. Its average elevation is about 150-200 metre above mean sea level. Comparatively, high area near Ambala forms the waterdivide between Indus and the Ganga. The average gradient from Saharanpur to Kolkata is 20 cm per km.

Origin of the Plain: It is almost universally accepted that this vast plain has been formed as a result of filling up of a large depression lying between the peninsula and the Himalayan region by the deposits of the rivers coming from there two landmasses. According to recent views, northern edge of the Peninsular plateau subsided due to its collision with the Asiatic part (when Indian plate collided with Eurasian plate). Thus, Great plains represent the infilling of the foredeep warped down between advancing peninsular block and rising Himalaya.

Geomorphology of the Plains (Relief): It is often said that Northen plains are monotonous, flat and featureless plain, but it appears to be a wrong notion. The plain has its own relief features which have their own significance. On the basis of relief features and geomoph-ological characteristics, following units of Northern plains are identified:

(1) Bhabhar Plains: It is a narrow belt (10 km. wide) running in east-west direction along the foot of the shiwaliks with a remarkable continuity from the Indus to the Tista. Rivers descending from Himalayas deposit their load along the foothills due to sudden break in slope, in the form of alluvial fans consisting of gravel and unsorted rediment. The porosity of people studded rocks is so high that most of the streams dissappear (by flouring underground). The bhabhar belt broades towards west and north west.

(2) The Tarai: This is a 15-30 km wide marshy tract in the south of Bhabhar running parallel to it. It is characterised by the re-emergence of underground streams of the Bhabhar belt. Due to gentle slope and defective drainage, water spreads over the surface converting the area into a marshy land. It is a zone of excessive dampness, thick forests, rich wild life and material climate. The Tarai is more marked in the eastern part than in the west due to higher amount of rainfall.

(3) Bangar or Bhangar Plains: The Bangar represents the uplands (alluvial terrace) formed by the deposition of the older alluvium and lie above the flood-limit of the plains. The alluvium is of dark colour and often impregnated with calcareous concretes known as ‘Kankar’. The alluvium of Bangar dates back to middle pleistocene age.

(4) Khadar Plains: The younger alluvium of the flood plains of the numerous river is called the Khadar or Bet (in Punjab). A new layer of alluvium is deposited by river flood almost every year, confined normally to the vicinity of the present channels. Its alluvium is light coloured and the clays have less Kankar.

There are two main relief features on the Indian plain- alluvial cones and fans and the intercanes- the intervening slopes between two cones. Alluvial cones are found with all the Himalayan rivers except the Ghaghra. The Bihar plain offers one of the best examples of alluvial cones and inter cones. The size of the cones varies from river to river depending on the volume of water and the load carried by the river.

Regional Division of the Northern Plains:

Though, the Northern plain is treated as a geographical unit with low elevation and gentle slope, its vast area exhibits distinctive physiographic and geomorphological characteristics in different areas allowing it to be divided into following four major regions:

1. The Rajasthan Plain: The western most part of the Northern Indian Plains is Rajasthan plain consisting of Great Indian Desert or Thar desert. About two-thirds of Indian desert lies in Rajasthan-West of Aravali range and the remaining one-third in neighbouring states of Haryana, Punjab and Gujarat. The desert proper is called Marusthali and accounts for greater part of Marwar plain. In general, the eastern part of the Marusthali is rocky while its western part is covered by shifting sand dunes locally known as Dharian. The eastern part of the Thar desert up to Aravali range is a semi-arid plain called Rajasthan Bagar. The Bagar has flat surface and in some parts it contains salt soaked playa lakes locally called as the ‘Sar’. The patches of fertile tracts in Bagar are called ‘rohi’. Luni river is the only living river in the arid plain, which is originated from Annasagar lake and is lost in the Runn of Kachchha. The tract north of Luni is known as Thali or Sandy plain. a part of the plain has also been formed by the recession of sea as is evidenced by the occurrence of reveral salt water lakes, e.g. Sambhar, Degana, Kuchaman, Didwana, etc. The Rajasthan plain has reveral dry beds of rivers (Saraswati and Drusdvati)

II. Punjab-Haryana Plain: To the east and north-east of Thar desert, lies Punjab-Haryana plain. Its eastern boundary is formed by the Yamuna river. It is characterised by flat, narrow strips of low-lying courses. Another relief feature is river ‘bluffs’, locally called ‘Dhaya’ which are as high as 3 metres or more. The northern part of the region adjoining the shivalik has been eroded by numerous revift and small streams called ‘chos’. The Punjab plain, a part of this plain, is primarily made up of doabs- the land between two rivers. From east to west these doabs are:

- Bist: between Beas and Satluj

- Bari : between Beas and Ravi

- Rachna: between Ravi and Chenab

- Chaj: between Chenab and Jhelum-Chenab

- Sindhsagar: between Sindhu and Jhelum-Chenab.

The area between the Ghaggar and Yamuna river lies in Haryana and is often termed as Haryana Tract, acting as water-divide between the Yamuna and Satluj rivers. In general, the Punjab-Haryana plain has two regional slopes- westwards towards the Indus river and southwards towards the Rann of Kachchha.

III. The Ganga Plain: This is the largest unit of the Northern Plains entending from the Yamuna river in the west to the western borders of Bangladesh or say from Delhi to Kolkata for a distance of about 1,400 km. It occupeis a total area of 3,57,000 sq. km covering the states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bangal. It is drained by the Ganga and its tributaries. All through, its course in the plains, the river is a braided stream bordered by low-lying depressions, which get flooded during rains. Physiographically, this plain can be sub-divided into following three divisions:

(i) Upper Ganga Plain: This part is bordered by Yamuna in the west and south and 100 metre cantour line (Allahabad-Faizabad railway line) in east. On the basis of Micro-level topographic facets, the upper Ganga Plain can be divided into three micro units:

(a) Ganga-Yamuna Doab: Situated between the Ganga and Yamuna rivers, it forms the largest Doab. The Yamuna-lower Chambal tract is notorious slopes between old Bhangar uplands and new Khadar lowlands are often quite pronounced with relative variations of 15 to 30 metres in relief and are locally called as Khols. Two distinct alluvial terraces flanked by two natural levees are identified in the Ganga and Yamuna and Yamuna Khadar.

Another prominent relief feature of upper Doab in the aeolian Bhur deposits, which denotes an elevated undulating piece of sandy land situated along the eastern bank of the Ganga in Moradabad and Bijnor districts.

(b) Rohilkhand Plain: East of Ganga-Yamuna Doab, it lies entirely in U.P. and is drained by Ramganga river. Here, Tarai in the north is quite extensive and presents a well-marked variation in Physical features.

(c) Awadh Plain: Ghaghara is the main stream of this plain lying east of Rohilkhand. Khadar of Ghaghara is very wide, because the river meanders through this area.

(ii) Middle Ganga Plain: It occupies eastern U.P. and Bihar, eastern boundary corresponding to Bihar-Bengal border. This is a very low plain, no part of which exceeds 150 m in elevation. The alluvial deposits have less Kankar. Besides Ganga, Ghaghara, Gandak, Kosi (in the north) and son (in the south) are other important rivers. The area is marked by local prominences such as levels, bluffs, oxbow lakes marshes, tals, etc. because the rivers flow sluggishly in this flat area. The relied features of entire Saryupar and North Bihar Plain are a series of alluvial cones and inter cones. A long line of marshes along Chhapra are known as ‘Chaurs’. On its outward side occurs vast lowlands called ‘Jala’ near Patna and ‘Tal’ near Mokama.

(iii) Lower Ganga Plain: It extends from the foot of Darjeeling Himalaya in the north to the Bay of Bengal in the south and from the eastern margin of Chhotanagpur plateau to Bangladesh-Assam border. This plain can be subdivided into:

(a) North Bengal Plain: Its eastern part is drained by rivers joining Brahmaputra (Tista-Sankosh, etc.) and western part by Mahananda, Ajay, Damodar, etc. This plain comprises Duars and Barind Tract (older delta of Ganga, which has been eroded into terraces).

(b) Bengal Basin (Delta proper): The heavily forested Sundarbans in the south and east Bhagirathi plain in the north are contrasting features. It is a relatively low-lying region wherein Bils, swamps, chars, levees, Dangas and coastal dunes are the only prominent physical features.

(c) Rash Plain : It is a low land to the west of Bhagirathi. It presents evidence of changing sea-level.

IV. Brahmaputra Plain: Also known as Assam Valley, this is the easternmost part of the Northern Plains. The plain extends from Sadiya in the east to Dhubri near Bangladesh border in the west. The region is surrounded by high mountains from all sides except on the west. Due to low gradient in Brahmputra is highly braided and has many riverine islands. Majuli is the largest slope from North-East to South-West towards the Bay of Bengal. The Assam Valley is characterised by steep slope along its northern margin, but the southern side has a gradual fall from the Meghalaya plateau.An interesting geomorphological feature is the isolated hillocks or monadnocks on both banks of Brahmaputra. Northern tributaries descending from Assam hills form a series of alluvial fans, which force the rivers to form meanders leading to formation of bils, ox-bow lakes, marshy tracts, etc.

Q10. Give a brief account of the second-order regions of Indian Peninsular Plateau. (2001)

Ans.

The Peninsular plateau consists of (1) Thar Desert, (2) Aravali Hills, (3) Central Vindhyan Uplands, (4) Khandesh and Satpura-Maikal ranges, (5) Chhotanagpur Plateau, (6) Meghalaya Plateau, (7) Kachchh and Kathiawar, (8) Gujarat Plains, (9) Konkan Coast, (10) Goa and Kanara Coast, (11) Kerala Coastal Plain, (12) Western Ghats, (13) Deccan Lava Plateau, (14) Karnataka Plateau, (15) Wainganga and Mahanadi Basins, (16) Telengana, (17) Southern Hills Complex, (18) Eastern Ghats, (19) Orissa Delta, (20) Andhra Coastal Plain and Delta & (21) Tamil Nadu

The Land to the west of Arawali is an arid waste called ‘Thar Desert’. The vegetation and soil cover are very scanty in this region. The Aravali Hills separate the desert from the Vindhyan Upland. The western slopes of the Aravalis are fairly rainy and forested. North of Ajmer, they are devoid of forest cover. The central Vindhyan upland comprising Malwa Plateau and Bundelkhand Gneiss and Vindhyan, Bharmer and Kaimur hills have been highly dissected and the soil cover is generally shallow. The vegetation varies from tropical dry deciduous to tropical thorny.

To the south of Narmada, the relief is dominated by steep sided Satpura, Mahadeo & Maikal ranges. Tapi trough has moderate thickness of alluvium. The Khandesh region lies in this alluvial basin interposed between Ajanta and Satpura ranges.

The Chhotanagpur Plateau east of son has varying attitude and high rainfall supporting a thick growth of tropical moist deciduous forest. The Meghalaya Plateau is even more dissected and humid covered with a variety of tropical wet evergreen forest.

On the western flank, the peninsular plateau has the outlying lava formations in Kathiwar and Kachchha. The Gir ranges in Kathiawar rise higher than general relief. The main features are however determined by dry climate supporting only a scanty growth of deciduous orthorny vegetation. The Sabarmati and Mahi as well as Narmada and Tapi river systems have deposited a thick layer of alluvium in the Gujarat plains.

The west coast consists of several segments. The Konkan coast is generally narrow. The Goa and Kanara coast is a transition zone between Konkanand Kerala coast. Climatically, it is a hot and humid region with the rainy reason lengthening as one approaches the south.

The Deccan Lava Plateau is flanked by the Western Ghats on the west. The Ghats are a continuous barrier all through, Thalghat, Bhorghat and Palghat gaps make cross communication possible. The ghats are generally forested with the character of vegetation changing from evergreen to deciduous varieties. The region presents a typical example of the rain-shadow effect. The soils derived from the weathering of lava rock formation belong to the famous black soil groups. The lavas of Deccan Plateau are replaced by gnisses and granites over the Karnataka Plateau.

To the east and north-east of Deccan Plateau lies the undulating plains and basins of Wainganga and Mahanadi. The rainfall of upper Mahanadi basin is generally higher than that of Wainganga Valley. The Sal forest of the Wainganga Valley is replaced by the teak forest in the Mahanadi basin. Telengana lying to the south-east ofDeccan is a low plateau highly denuded and dissected. Its southern part is mainly an expanse of tropical grasses of Savannah types. The Southern Hill complex includes the Nilgiris, Anamalais and the Palni/Cardomom group. Being a region of complex relief, these hills are further distinguished on the basis ofa rich growth of forests, particularly teak andsandalwood.

Eastern Ghats are a discontinuous line of hills bordering the peninsular interiar. The northern hills are more forested than the southern. The east coast of India has three main segments-Orissa Coast, Andhra Coast and Coromandel coast of Tamil Nadu. In Orissa, wide deltaic plain of Mahanadi and Brahmani are generally moist and forested in parts. Andhra coastal plain show the tansition between S.W. and N.E. monsoon regimes. The coromandel coast has its own rainfall ragime determined by North-East monsoon. Entire eastern coast is the main area of population agglomeration based on fertile alluvial soils.

Q11. Explain the sequence of vegetation zones of the Himalayas. (2001)

Ans.

Altitude has profound impact on the sequence of vegetation zones in the Himalayas. This is because of the reason that with the increase in the altitude the temperature goes on decreasing. The Himalayas rise abruptly from the tropical heat to the heights of arctic cold. Therefore, there exists a sequence of vegetarian zones- from tropical to tundra in the Himalayas. Moreover, the eastern Himalayas are placed relatively near the tropic of Cancer and oceanic area while western Himalaya are located in relatively cool and dry continental climate.

(i) The Eastern Himalayas:

Tropical wet everygreen and semi-everygreen forests are found up to a height of about 900 metres. The forests are dense and luxuriant and of mixed type. Sal, Shisham, Khair and Toon are fairly common is the tarai. The forest has a rich undergrowth of shrubs, ferns and grasses. Bomboos are common, climbers and epiphytes are found everywhere.

Between 900-1,830 metre altitude zone subtropical wet hill forests are found. Pines and broad leaved oaks are the common trees. In east Assam and Khasi Hills, Pinus khasya occurs gregariously. Undergrowth is almost absent in Pinus khasya forests. Above 1,830 metres up to a height of 2,750 metres monsoon temperate mountain forests of mixed vegetation exists. The trees are broad leaved. Oaks, laurels and chestnuts are common trees. Birch, maple and magnolias are other trees.

At an elevation higher than 2,750 metres, conifers replace broad leaved temperate vegetation. Silver fir and Spruce are now more common trees and Juniper and Rhododendron most common shrubs. Between an altitude of 3,650 and 4,875 metres, spreads the zone of alpine vegetation. Ascending above 3,650 metres one passes through a belt of scrubs and highly dwarfed vegetation consisting of Rhododendrons, Williows, Junipers and primroses. Above the Alpine vegetatin i.e. between 4,875 and 5,100 metres is found the zone of Tundra vegetation characterised by stony warte with lichens and few herbs.

(ii) Western Himalayas:

In contrast to eastern Himalayas, epiphytes and ferns are not found in the western Himalayas. Instead of luxuriant tropical vegetation, dry, savanna is dominant over vast areas in the foot hills. However, in Garhwal Himalayan foothills where rainfall is higher, Savanna and mixed tropical deciduous forests are found. Acacias, Sisso, Saland Semal are common trees. This tropical vegetation is replaced by sub-tropical one above on altitude of 900 metres up to 1,500 metres having mixed forest. Chir is a conifer which occurs at height between 900 metres and 1,500 metres is gregarious and yields resin and timber. The monsoon temperate belt is lower by about 300 metres in the western Himalayas situated between 1,500 and 3,350 metres. Conifers- deodar (2,000-2,600 metres), silver fir (2,450-3,350 metres), blue pine (2,150-2,600) – are important timber trees. Alpine vegetation in western Himalayas is found between 3,350 and 4,750 metres. In the dry interior valleys north of the great Himalayan range plants grow sparsely.

Q12. Elucidate the mechanism of the Indian Monsoon. (1999)

Ans.

Monsoons originally applied to the winds over the Indian ocean characterised by the seasonal reversals in the atmospheric pressure and wind system. Various explanations have been offered for its origin and mechanism:

Thermal Concept: This was first suggested by Halley who considered Monsoon as land and sea breezes on a gigantic scale. With the apparent northward movement of the sun, intense heating results into vast low area, from North West part to Tibetan highland, which attracts winds from Indian ocean as South-West Monsoon flow. This condition is reversed in winter and North East Monsoon flows from the Indian sub-continent.

Dynamic Concept: Flown proposed that Monsoon are nothing but a continuation of equatorial westerlies which upon crossing the equator takes a South West direction under coriolis force. This happens when Inter Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) shifts northward during summer.

Recent Understanding:

(1)Jet Stream: According to M.T. Yin, the abrupt onset of the summer Monsoon is related to the sudden northward shift of the sub-tropical westerly jet stream from the Himalaya which leads to a reversal of the curvature of flow of free air to the North West of the sub-continent. The simultaneous establishment of Tropical Easterly Jet Stream along Kolkata-Banglore axis maintains monsoonal circulation.

(2)Tibetan Highland: Due to intense heating, the vast Tibetan highland acts as a heat source from where air move up and diverges leading to anticyclogenesis in upper-troposphere. Embedded in the equatorward limb of diverging air is the Tropical Easterly Jet. This diverging air finally Descends over Mascarene high, about 25° South, intensifies its high pressure cell so as to move as South West Monsoon, Thus completing The modified Hadley cell.

(3)Teleconnection Between Ocean Bodies: Scientists have tried to find out the intricate and complex relationship between Indian Monsoon and EL NINO, Southern Oscilation (SO) and Walker cell.

El Nino, often associated with bad monsoon, is the appearance of warm ocean current in place of cold peruvian current leading to large atmospheric perturbations. In Southern Oscillation, discovered by Sir Gilbert Walker, Whenever the suface pressure is high over the pacific, the pressure over the Indian ocean tend to be low (Positive So) and vice versa (Negative SO). There is close relationship between appearance of El NINO and negative SO, collectively called ENSO event.

When there is positive SO, the air rises from the low pressure area over South East Asia and Australia, turns eastward and after traversing Pacific descends over South America to be moved again towards Australia, thus completing the cell known as Walker cell. Probably due to intense cloud cover over S.E. Asia or some other reasons, in some years this pattern is reversed, EL NINO sets in and a larger area over Indianocean becomes a zone of descent rather than ascent leading poor monsoon and drought conditions.

Q12. Explain the rise of the Himalayan ranges. (1999)

Ans.

As per postulates of Plate Tectonics, The origin and rise of mighty Himalayas is the result of collision between the Indian plate and Eurasian plate, both of which now contain continental portion along the collision boundary (a continent-continent collision). The major events can be summarised as follows:

- The wedge of sediments occurring along the margins of Indian and Eurasian plate were deformed as Indian plate carrying Gondwanaland began to move towards Eurasia.

- As collision proceeded the oceanic crust descended into the mantle (the subduction process) and melted leading to explosive volcanism.

- The total consumption to oceanic crust brought the continental crust of Indian craton in collision with that of Eurasian continental crust. Subduction stopped and volcanic activity ceased.

- Instead of subducting, leading continental edge of Indian plate was forced to thrust under Asia, generating a double layer of low density continental material which rose buoyantly. This process partly accounts for the high elevation of Himalayas and the Tibetan plateau.

Evolution: The upliftment (rise) of the Himalaya was accomplished in a series of five impulses punctuated by intervals:

- The first upliftment took place in late Cretaceous-early Eocene time along the northern border of the mountains leading to a palaco-island arcsystem. The evidence of such volcanic activity is found in the Dras-Kohitan range.

- The second upliftment starting in late Eocene time resulted in deformation of Tethyan Himalayan zone and emplacement of granite and granite gneisses that comprise the higher Himalayan zone.

- The third upheaval taking place in Middle Miocene deformed the rocks of lesser Himalayan zone.

- The fourth upheaval took place in Pliocene-Pleistocene epoch raising the Hamalayan foothills.

- The fifth and final phase comprised the receding of Pleistocene glaciers and resultant isostatic upliftment. This upliftment due to isostatic adjustment is still in progress.

Q13. Evaluate the feasibility of the proposed Ganga-Cauveri drainage link. (1998)

Ans.

Ganga-Cauveri drainage link is part of the several links proposed recently for inter linking the rivers at national level. The present proposal assumed unprecedented significance in the backdrop of directive recently given by Supreme Court during a hearing of contentious Cauvery water dispute case and also because of severe drought experienced in 2002.

The idea proposed is to link the major rivers of whole India so that floods can be mitigated from the diversion of excess water in the north to the drought-hit proposal, needs a thorough the national perspective plan for inter-linking the rivers.

Major Feasibility Concerns: Well, there has been arguments and counter arguments, sides speaking for and against the proposal of this mega-project. On the face of it, the proposal sounds attractive to the extent that the principle of mutual resource sharing amongst the regions will meet the increasing sectorial demand of water but the aspects which the recently appointed task force, will have to look into are technical, political, economic and ecological.

The engineers have opined that technically the project is by and large feasible. What has to be borne in mind is that the terrain over which the link (Canals/tunnels) has to be built is not a flat one rather varied, comprising of plains, plateaus and hills. Moreover the lifting of 1500 cubic mitres of water per second will not be able to reduce the volume of floods in Ganga basin as flood discharge is much larger than the envisaged capacity of pumping.

Economically, to make more than 1000 km. of link canals, more than 200 storage reservoirs and generation of about 10,000 MW of electricity will have serious resource implications. The total financial estimates, according to experts amounts to a sum of Rs. 500,000 crores which is not small for a developing country like ours.

Feasibility concerns of political nature will have to be given due attention. We have already the extent of resistance and painful aspect of displacement in the Narmada and Sardar Sarover project, apart from the violent tension between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu on the Cauvery-water issue. Emphasis should be placed on evolving consensus among the states on these complex issues.

Concerns regarding ecological feasibility of this mega-project can not be overlooked also. Any inter-basin transfer of water has to cut-across the water divide. The recipient soil type may react differently to the organic and inorganic material of alien water. Areas under Indira Gandhi canal project are facing serious problems of water logging, salinization and alkalization. The pertinent question is- what will be the strategy for distribution of water and in what amount? The whole project will involve large scale deforestation, alteration of slopes, destruction of natural halrtat, etc. Such environmental consequences have to be minimized by careful formulation and implementation of the plan and rectifying measures will have to be taken simultaneously for making the proposal of the mega-project feasible.

Q14. Draw a sketch-map in your answer-book to delineate the main climatic regions of India and discuss the important climatic characteristics of each region. (1996)

Ans.

Although broadly speaking India’s climate is of tropical monsoon type but large size and physical variations have created climatic variety at regional level. Several attempts have been made to divide India into various climatic regions. Treewartha’s classification of climate which is in itself a modified form of Koppen’s scheme corresponds with the vegetative and even geographical regions of India in a fair manner. Here treatment of climatic regions is based on the Treewartha’s scheme. Four major climatic groups (A,B,C, and H) which are further sub-divided into seven climatic types have been recognised and are as follows:

A.Tropical Rainy Climatic Group:

- Am—Tropical monsoon rain-forest

- Aw—Tropical wet and dry dlimate or monsson savanna. It is further sub-divided into two parts.

- North-East Indian Plateau Type

- Tamil Nadu Type

B.Dry Climatic Group:

- Bs—Tropical Steppe (semi-arid)

- Bsh—Tropical and sub-tropical steppe

- Bwh—Tropical and sub-tropical desert

C.Humid Mesothermal Climatic Group:

- Caw—Humid sub-tropical with dry winters. It is further sub-divided into two parts

- Caw eastern type

- Caw western type

D.Mountain Type:

Each of seven climatic regions have been discussed below:

- Tropical Monsson Rain Forest (Am): It is characterised by average annual temperature of 27°C and annual rainfall exceeding 250 cm. April and May are the hottest months with normal mean maximum around 23.7°C. The rainfall is seasonal, from May to November, and is adequate for the luxuriant growth of vegetation in the form of tropical wet forests. This climatic region is spread over Western Ghats, Tripura and Southern Assam.

- Tropical/Monsson Sawanna (Aw): This climate is enjoyed by most of the Peninsular Plateau excluding the semi-arid tract in the rain-shadow region of Western Ghats. This climate has a marked dry season. The average annual temperature is 27°C and the annual rainfall is 100cm. Being almost out of the influence of western disturbances, there is very little rainfall during winter except in Tamil Nadu and adjoining parts. Hence Tamil Nadu and adjoining coastal areas are separated as a sub-region and designated as Tamil Nadu Aw climate.

- Tropical Semi-Arid Steppe Climate (Bs): Here average annual temperature is more than 27°C but amount of annual rainfall varies from 40 to 75 cm. Under such rainfall conditions only grasses with a few scattered trees form natural vegetation. This climatic region comprises the rain shadow areas of Western Ghats occupying central Maharashtra, Karnataka, interior Tamil Nadu and Western Andhra Pradesh. Low and highly unreliable annual rainfall makes this region better suited to grazing of cattle and less to permanent agriculture.

- Tropical and Sub-Tropical Steppe (Bsh): This is a semi-arid region covering parts of Gujarat, eastern and central Rajasthan and Southern Haryana. Temperature conditions resemble those of the desert but with less extremes. Average annual temperature is more than 27°C. The annual rainfall is generally between 30 cm and 65 cm. But the rainfall is highly unreliable. So the people either grow bajra and jowar or graze their herds of sheep, goats and cattle over uncultivated area that grow short coarse grasses to supplement their income.

- Tropical and Sub-Tropical Desert (Bwh): It occupies western Rajasthan and Kachchh region of Gujarat. The rainfall is scanty, less than 30 cm annually or and sometimes even less than 12 cm. Vegetation is in the form of thorny bushes. During summer season the temperature is as high as 48°C while in winter it drops to 12°C showing high seasonal and diurnal range of temperature. Owing to extreme aridity this region is sparsely peopled except in the north where canal irrigation is available.

- Humid Sub-Tropical Climate with Dry Winter (Caw): This climatic region comprises the foothills of Himalayan part of Punjab-Haryana plain, East Rajasthan (east of Arawali), the plains of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Northern West Bengal and Assam. Here average temperature of the winter season is less than 18°C but reaches 46°C to 48°C during summer. Annual rainfall is about 65 cm in the west. It increases to the east and towards the Himalayas. In north-east Assam, it is over 250 cm a year.

- Eastern and Western part of this climatic region, due to heavy rainfall in the east, exhibit wide differences in the natural vegetation, cultivated crops. Hence this climatic region may be sub-divided by an isohyet of 100 cm into two types—Caw eastern type and Caw western type.

- Mountain Climatic Type (H): This region includes the entire Himalayan belt from Kashmir to Arunachal Pradesh. Here average temperature of June lies between 15°C and 17°C but during winter season it falls below 8°C. The rainfall decreases from east to west and in areas of high altitude it is in the form of snowfall. Western parts also enjoy rainfall during winter season by temperate cyclones.

Q15. Examine the origin and characteristics of the antecedent drainage system of the Himalayas. (1996)

Ans.